It has been 40 years since the Centers for Disease Control in the United States identified the first cases of what was to become known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS.

A year later a man in Sydney was the first person in Australia to die of AIDS. We have learnt a lot over the course of the last 40 years, and the most important part of what we learnt then, is being deployed now with the current COVID pandemic; the power of a mobilized community.

Australia was fortunate in that it was recognised as early as 1983 that the only way to respond to the emerging pandemic of HIV was to act collectively.

The Power Of Community

First there was the Victorian AIDS Action Committee, then there was the Victorian AIDS Council. It was from a tiny basement office in King William Street Fitzroy that the earliest prevention initiatives were born and the first care and support teams were deployed to help people living with HIV, and those suffering from AIDS deal with the formidable challenges they had to face.

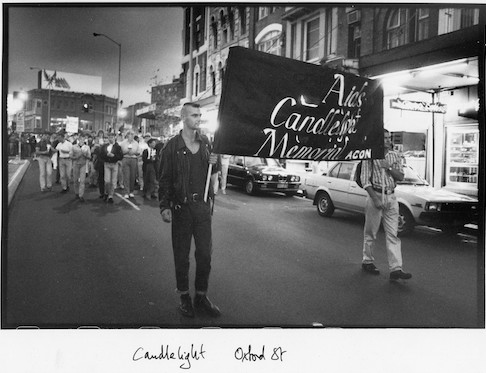

Bigotry, homophobia, poverty, illness, disease, death, stigma and discrimination were commonplace and it was the community who not only responded to those challenges but also mobilized with mass demonstrations, strategic civil disobedience, along with clinical and political partnerships to fight for better care and treatments for people living with HIV and AIDS.

It was the community who decided to act. It was gay men who decided that we needed to use condoms to fight a pathogen that was not fully understood at the time. And it was the broader LGBTI community that volunteered to fundraise, transport, work in prevention, nurse, care and support those in need that really made a difference then, and now.

A Seat At The Table

It was fortunate that in Australia we did not have to fight for a seat at the table. From the outset, community was seen as pivotal to an effective response to HIV and AIDS. We sat on ministerial committees, research working groups and were critical to the care and support needs of all those affected by the pandemic, regardless of whether they were living with HIV, battling AIDS or were lovers, friends and family of those who were. For us it was, and is, personal.

At the time, and since, in some parts of society we were characterised as incurring the wrath of God — we were paying the price for being promiscuous degenerates. Since the vast majority of people living with HIV and suffering from and dying of AIDS in this country have been gay men, it often meant fighting for support and understanding from the broader community, who were willing to characterise the disease as a ‘gay plague’ and ‘not their problem’.

This did two things simultaneously. It fed the pervasive stigma associated with HIV that exists to this day, and it sidelined, and in some cases erased others who were living with HIV and AIDS. Women, heterosexuals, haemophiliacs and children were often only mentioned as innocent ‘victims’ of the ‘gay plague’.

It has taken over 40 years of insisting that no one with HIV is a ‘victim’ to arrive at a place where it is recognised that all people have a right to dignity, respect and agency in their own health and wellbeing, regardless of their sexuality, gender, race or cultural background.

Community was integral in the research effort that enabled the 1996 announcement in Vancouver of successful combination therapy for HIV that ultimately led to HIV becoming a chronic manageable infection. This was unprecedented.

From A Pandemic To A Manageable Infection

Prior to 1980 the disease was unreported. The speed at which clinical research, supported and in many cases guided by community, meant that within two decades HIV became a manageable infection and the incidence of AIDS in developed nations has been dramatically reduced.

There is still much work to be done. While it is true that in developed nations with good healthcare and infrastructure that facilitates awareness, testing, treatment, care and support can reasonably be expected to meet epidemiological targets aimed at the elimination of HIV, developing countries have no such comparable structures. HIV and AIDS remain a very real problem in eastern Europe, central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa.

In our own country, we are seeing the emergence of new infections in populations of people from non-English speaking backgrounds and overseas born students. Breaking down the barriers of stigma, isolation and fear to health promotion, testing, diagnosis and treatment in these populations are challenges that we must meet.

There is evidence that the emergence of HIV was the result of cross-species infection, from animals to humans. Now we are facing another global pandemic which is said to have similar origins.

There are obvious differences between COVID and HIV, but the spirit and strength of the remarkable community response to HIV over the last 40 years can impart many invaluable, life-saving lessons to the challenges we face today.

Colin Batrouney is the Acting CEO of Thorne Harbour Health. Colin is also Thorne Harbour Health’s Director of Health Promotion, Policy and Communications.