Slipping through the cracks

WARNING: This article contains material about suicide and sexual assault and may be distressing to some readers

MENTAL health issues impact all sectors of society. While this touches everyone’s lives, LGBTI youth are disproportionately affected.

Rates of depression, self-harm and mental illness vary from four to 14 times the rates for their heterosexual peers. These rates often stem from experiences of anxiety of coming out, or discrimination, rejection and bullying via the family unit, schools, religious institutions, work or peers.

However, there are those in the LGBTI community that will not accept these disproportionate rates as the norm. Some have researched extensively and helped produce recent reports such as Growing Up Queer, and the beyondblue and PLFAG collaboration Families Like Mine, or worked behind the scenes to help make the Safe Schools Coalition become a national initiative.

On the other hand, there also organisations that directly represent LGBTI youth in every state and territory in Australia, doing their work in a largely unsung and — unfortunately — underfunded manner.

Queensland’s Open Doors, Victoria’s Minus18 and NSW’s Twenty10 all work to support LGBTI youth 26 years and under and advocate for them directly. Homophobia and transphobia at home or school, family breakdowns and reconciliation, homelessness and mental health are just some of the areas that these youth organisations deal with on a daily basis.

The young people they’ve helped are eager to sing their praises.

Scha, 25

COMING from Malaysia to Brisbane as a part of a university scholarship program in 2010, Scha was thankful to be in a country where she could start to properly explore her gender identity and finally express herself, away from a family that had at times made their disapproval of her identity painfully known.

“Trans* people are really brought down in Malaysia and treated like scum. It’s a very conservative Islamic country and I experienced that almost daily,” Scha said.

“I’ve occasionally been physically assaulted while growing up as a very effeminate boy and once my father even beat me up when I was four, saying stuff like, ‘why are you walking that way?’”

Scha first came into contact with Open Doors through one of their social events, Queeriousity, and through them, was able to learn about trans* issues and transitioning itself.

After being involved with the organisation for a while, she started to feel comfortable enough wearing feminine clothes when coming along to Open Doors ‘drop in’ days. With their assistance, Scha also started to undergo her transitioning process last year.

She also was granted a protection/humanitarian visa on the grounds of being a trans woman who would face discrimination and persecution in Malaysia.

Lawrence, 20

LIVING with mental illness from a young age, at one stage Lawrence Chang was seriously considering self-harm and suicide.

Living in Melbourne and coming from a Chinese and Cambodian family, Lawrence said their acceptance of his sexual orientation was difficult.

“I told my family in my late high school years, as being in a culturally and linguistically diverse background it was a terrible experience. My parents didn’t understand what being gay had meant, as no one in the family lineage was ever known as a homosexual,” he said.

Lawrence started going along to Minus18 when he was about 15 after being directed to the group by his school counsellor — who happened to be the first person he came out to — and described it and an important supportive factor in his life: “I met a lot of people there, some I still keep in contact. It was amazing to have an organisation that supported queer young people, especially at that age.”

* * *

FOR many LGBTI youth, family homophobia and transphobia can be devastating, as it can potentially damage a crucial supportive structure.

Findings from the recent Growing Up Queer report from the Melbourne-based Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre found that rejection from home often resulted in young people choosing to leave, or in worst-case scenarios, being thrown out.

Scha started to experience transphobia from her family at the age of four and has kept news of her transitioning away from her parents, despite still being in contact with them.

“Like many Asian cultures, there is a huge emphasis put on family, so not being able to be completely honest with my parents really is hard sometimes,” Scha said.

“Because of the visa I may not be able to go back to Malaysia at all. I sometimes think what will happen if they pass away never knowing who I really am. It’s a really tough struggle, it’s really horrible.”

According to the report, some LGBTI youth ended up in foster care or living in youth refuges and also reported experiencing suicidal thoughts and attempts, self-harm and depression.

Due to her own mental health issues, Lawrence’s mother was physically abusive towards him from a young age and for his own safety he was placed in foster care, which he actually credits as being very beneficial for him.

“My foster care experience was great… I think I told some of my carers that I am same-sex attracted and that didn’t really infringe on our relations,” Lawrence said.

“My mental health improved while living in foster care, it was much more easier than living at home. Staying there any longer would of been detrimental to my mental health.”

* * *

OFTEN as a result of family rejection, some LGBTI youth are either thrown out from home or choose to leave for their own well-being and safety.

Many participants in the Growing Up Queer report had left home before the age of 18 and accessed various government-housing services that included short-term and emergency accommodation along with foster placement.

Respondents often experienced multiple placements, each varying in positive and negative experiences, which also resulted in changing schools and interruptions to education.

Being open about sexual or gender identity in certain housing situations can present many LGBTI youth with dread or anxiety.

According to Open Doors, several young people that they look after have experienced homophobia and transphobia by other youths sharing non-LGBTI specific temporary living arrangements, or by housing staff and some religious homeless youth organisations.

“Some of our young people have had horrendous times in some hostels and other housing situations based on their sexuality or gender. Of great concern is that sometimes we’ve heard of staff being verbally abusive and some treating young trans* people very poorly,” Open Doors coordinator Rocky Malone said.

Due to being in a Malaysian Government scholarship program, Scha felt she could not completely express her identity for fear of having her education terminated along with accommodation that came with the scholarship. This prevented her from reporting two instances of rape.

“I couldn’t report it because I live with the other Malaysian students and I didn’t want to cause any problems,” she recalled.

“I wasn’t out at all with any of the other students and I just couldn’t tell anyone. It was horrible.

“I knew that if I had reported it I would have been in trouble. There was another student in our group that was expelled from the scholarship by the Malaysian Education Department for being gay. I was left to deal with it by myself.”

Meanwhile, Lawrence experienced homelessness first hand.

“I couch surfed between late 2011 and early 2012, where I found refuge in a Scout leader’s family home,” he said.

“I eventually found a share house I could move into, which I had lived in for about roughly six months until my mental health deteriorated.

“I was displaying signs of suicidal tendencies and the stress from my life, at the time was really overwhelming. I was hospitalised in October, but moved on to living in a rehabilitation residential support service in Mont Albert between late October to early December.

“[After I left rehab] I had couch surfed and often visited Frontyard homeless youth services where they provided me accommodation in various refuges and backpackers hostels.”

Lawrence found that being open about his sexuality during the time that he was homeless was not a desirable thing to do.

“I didn’t disclose my sexual identity while I was homeless. I didn’t feel that it was necessary to talk about my sexuality, I had other far greater things to worry about such as finding somewhere to stay the night,” he said.

“I also didn’t feel comfortable telling people this, it wasn’t the best community to be around.”

According to Open Doors, Minus18 and Twenty10, due to a lack of specific research on LGBTI youth homelessness getting an accurate idea of it proves difficult.

“Much more research is needed. The extent to which young people are homeless or at significant risk is difficult to measure,” Twenty10 executive director Brett Paradise said.

“Solid research does not come cheaply and funding available is scarce. Accessing any group of vulnerable people is difficult. Young homeless people are unlikely to be in a position to participate in research and it there are many ethical considerations in asking this group to participate.”

Paradise’s Queensland counterpart agrees that funding is a major factor that holds back homelessness information.

“We would love to have a better idea of how many young people are experiencing hardship with living situations and use that information to improve our services,” Malone said.

“Unfortunately the funding just isn’t there.”

* * *

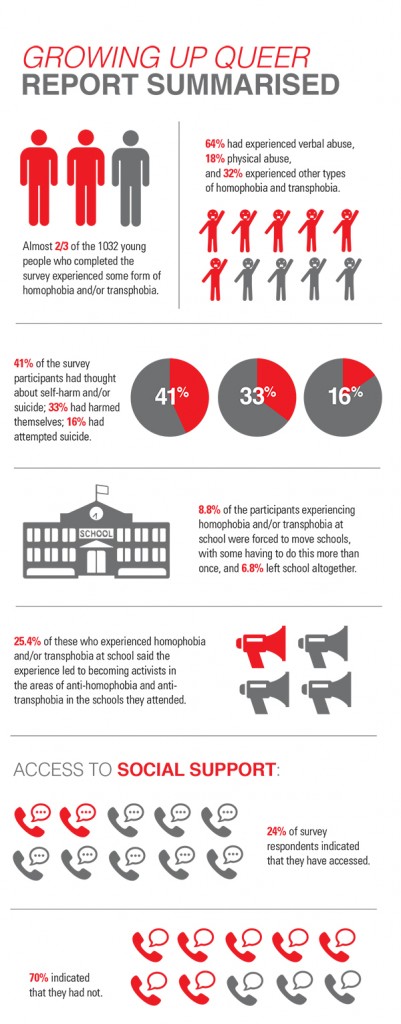

THE findings of Growing Up Queer highlight the impact that homophobia and transphobia and can have on the general health and wellbeing of LGBTI youth.

Of great concern is that among report participants, 41 per cent had thought about self-harm and/or suicide, 33 per cent had harmed themselves, while 16 per cent had attempted suicide.

Many participants also experienced frequent and consistent harassment, violence, isolation from peers, and rejection from families. This often resulted in feelings of “despair, of being alone and of internalised homophobia or transphobia”.

For Scha, being targeted and humiliated at school took its toll.

“There was a religious class teacher who used to publicly shame me in class. Sometimes he’d ask me where my bra was,” she recalled.

“When I was 17, I had a teacher openly ask me during class whether I was a boy or a girl. I often left class in tears.”

Again highlighting that she was limited in how much she could stand up for herself and report abuse, Scha found herself subjected to sexual abuse during her boarding school years in Malaysia.

“I couldn’t report anything about it for fear of getting in trouble. I already felt I was causing enough problems by being a very effeminate boy,” she said.

“It was incredibly difficult for me to deal with.”

Still a practicing Muslim, Scha found herself praying to be the boy everyone around her expected.

“I actually prayed to God in Mecca asking him: ‘if you don’t want me to be this way then change me tomorrow and I’ll be fine with it.’ But when that didn’t happen the next day I thought, ‘I guess he wants me to be this way’,” she said.

For Lawrence, mental health is still something deals with.

“Mental health issues have played a massive role in my life, as such it has taken me to a point of near death, and to where I am now,” he said.

Unfortunately, for all of the issues raised that face our LGBTI youth, no clear solution exists. Homophobia and transphobia are not going away anytime soon.

As for the community, gaining a better understanding of what they face and offering a supportive hand through organisations such as Open Doors, Minus18 and Twenty10, will present vulnerable LGBTI youth an opportunity to excel.

“[Minus18] played a major role in helping me come out to my community. It had a lot of resources and presented a safe space for queer young people,” Lawrence said.

Scha agreed: “I believe that organisations like Open Doors are germane to LGBTI youth’s wellbeing — especially for those who are deprived of support and love by their family or society at large. For me, Open Doors is my Aussie family. Where I learned about self-love and the importance of being surrounded by support.”

Support is available for anyone who may need it. Phone Qlife 1800 184 527; Lifeline 13 11 14 or beyondblue 1300 22 4636.

**This article first appeared in the August issue of the Star Observer. The September issue will hit the streets this Thursday (August 21) in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Canberra. Click here to find out where you can grab your free copy.