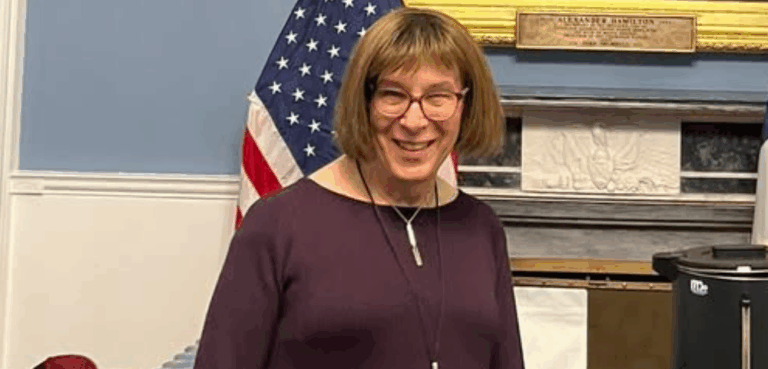

‘In rural communities LGBTI people are often denied or invisible’: Starlady

Community activist Starlady has been a longtime champion for trans and gender diverse Australians. Matthew Wade caught up her to chat about her vital work in regional and rural Australia.

***

What were your early experiences of regional Australia like?

Growing up as an ‘out’ queer youth in regional Victoria in the late eighties and early nineties was brutal, homophobia was rampant. The violence I experienced really shaped my youth and gave me a tremendous drive to be an agent of change. How do you describe an era without access to the internet, access to the queer community, or access to queer theory where there was an incredible pressure to conform?

What prompted you to start working there?

In the early noughties I left the inner city queer neighbourhoods to engage in environmental and human rights activism in outback South Australia and the Northern Territory. The desert was full of adventures from protests against the Iraq wars at Pine Gap to the historic protests at the Woomera Detention Centre.

My most significant experience was walking from Lake Eyre to Sydney in 2000 on a peace and healing walk with Arrabunna elder Uncle Kevin Buzzacott. I learned about the invasion and developed a greater sense of cultural awareness in working with Aboriginal communities. Years later I returned to the desert to deliver hairdressing and fashion workshops in remote Aboriginal communities.

What kinds of issues do LGBTI people face in those areas?

The Northern Territory government provides very little funding to support the LGBTI community and there were no specific LGBTI services while I lived there. We know that LGBTI people live in all communities but often in regional and rural communities our identities are denied or rendered invisible.

It’s hard living in environments where you aren’t seen or recognised, because it impacts your health and wellbeing. Accessing trans healthcare can be difficult within the city, but in many regional areas those healthcare pathways simply do not exist. The health and safety of trans and gender diverse people living in regional communities who want to medically affirm their gender identity can be put at significant risk when they are unable to access the basic healthcare to meet their needs.

As an unashamedly queer person, how were you received when you travelled to those areas?

There was a really vibrant LGBTI community in the Northern Territory, including sistergirls and brotherboys. I drew a lot of strength from the people around me. The area has a history of outcasts and rebels, and in many ways I really thrived in that environment, where the most admirably quality was authenticity. In the Northern Territory it didn’t matter how you looked, it was about your skills and if you walked through the world with a kind heart.

What’s something you learned through your work out there?

I learned to be more open to the diversity of the human experience. In the city we can become really ghettoised, where we only associate with people who have similar ideas to our own. The age of social media has really polarised our society. In the Northern Territory we were almost forced to get along and to connect despite our differences, and this has the potential to create healthier communities.

Do you think issues affecting regional and rural LGBTI Australians are often left out of the conversation?

I believe LGBTI communities in inner-city metropolitan areas can at times be out of touch with some of the experiences of people living in rural and regional communities. Just because we have equal marriage now doesn’t mean everything’s just rainbows and lollipops. For those of us who live in the city it’s valuable to reflect on our own privilege and be aware that we may have greater access to services, communities, and relationships that are not accessible to many living elsewhere.

What’s your fondest memory in the outback?

I miss Areyonga, the community where we made the documentary Queen of the Desert. Whenever I arrived there all the kids would come running out of their houses chanting my name, asking me if I’d brought their favourite hair colors. I was really celebrated and loved in that community.

How can we further help or support LGBTI people living in regional / rural Australia?

I feel it’s vital that we build healthcare pathways for trans and gender diverse people living in regional and rural Australia. Our healthcare system currently pathologises gender diverse people where extensive medical ‘approvals’ are often required to medically affirm your gender identity.

I’d highlight the great work of Gateway Health Gender Service in Wodonga which is the first regional trans and gender diverse health service in regional Australia. The service actively engaged the trans and gender diverse community in consultation as it developed its service and has a great community reference group. We need to ensure that services such as these receive ongoing funding and support, it’s a model that could be reproduced across regional Australia.