The Sunshine State’s darkest chapter

“I AM against the dirty and despicable acts these [homosexual] people carry out. You can’t get any beast or animal that is so depraved to carry on the way they do.”

Queensland’s early response to the HIV and AIDS epidemic was set back for years by the actions of the man quoted above: Joh Bjelke-Petersen — the state’s former premier and one of the country’s most controversial.

In the 1980s, the gay community across the country was mobilised to address the epidemic and in most states, it was given a key role in the country’s response: a role that was supported by state and federal governments who encouraged a partnership approach between key stakeholders. It’s a response that has long been credited as defining best-practice for health authorities both here and around the world.

However, not every state contributed to this pioneering response. In Queensland the government of Bjelke-Petersen would have no part in what the rest of the country was doing to prevent the deaths of people living what he called “a degenerate lifestyle”.

Earlier this year a release of cabinet documents from 1985 prompted a review of the epidemic’s history in Queensland — documents that revealed the extent at which the Bjelke-Petersen government went to prevent an effective response, essentially leaving the state’s gay community to fend for themselves in their greatest time of need.

Homosexuality was also still considered a crime in Queensland throughout the 1980s, which added to the challenges the community faced.

Phil Carswell is an Order of Australia honouree for his work in the HIV sector at the beginning of the epidemic in Victoria who also played a crucial role supporting the establishment of the Queensland AIDS Council (QuAC) in October 1984.

“Given the hostile environment, the gay community was not particularly large or well organised so when AIDS arrived, there was a very small pool of people ready and able to fight for what was taken for granted in other states,” he recalled.

“In terms of the gay community itself, I was told of people being arrested outside gay venues, strip searching on the street and examples of young gay men stopped outside venues, being interrogated and when they revealed that they had engaged in gay sex, being arrested and subsequently jailed.

“The evangelical homophobia of the Lutheran Premier and his cabinet gave free rein to the basest forms of homophobic violence in the police, media and the wider community.

“Understandably, gay men and lesbians either retreated into the closet or escaped south as soon as they could.”

QuAC formed with 14 members amid an atmosphere of paranoia and fear, and within a few months it was publishing material on safe sex practices — years before official health bodies did it themselves.

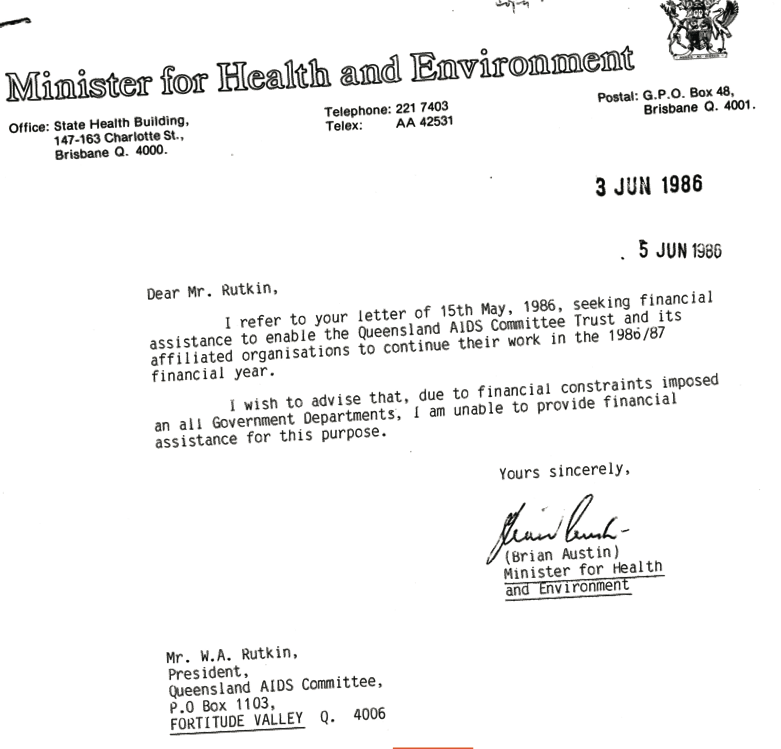

However, funding for the newly-formed organisation was impossible to come by at a state level, and commonwealth funds had to be passed on in secret — via brown paper bags — by the Sisters of Mercy and Sister Angela Mary.

The release of the 1985 cabinet documents only reaffirmed the dark chapter in Queensland’s early response to HIV and AIDS.

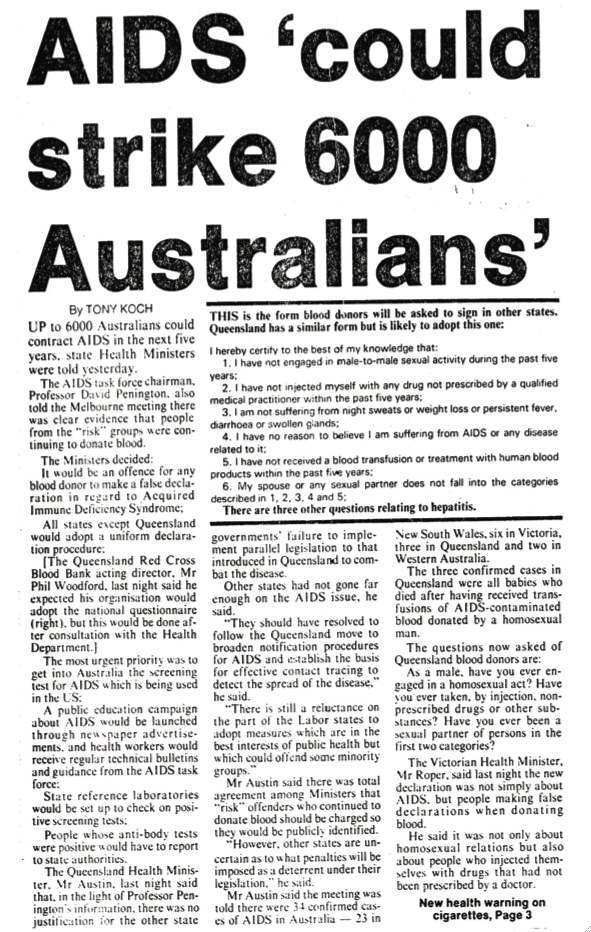

For example, the minutes reveal how the cabinet considered the issue of AIDS during eight meetings throughout 1985 and what it could do to prevent the its spread in Queensland.

An incident at a Sydney pool that hosted an event for the Sydney Mardi Gras sparked national concern over how HIV was transmitted.

“As a parent, I would have strong reservations about letting young people compete in a pool that was used for such a sick event as a gay swimming carnival,” Queensland’s welfare, youth and ethnic affairs minister Geoff Muntz said at the time.

“It seems these people who promote such an immoral, unnatural and deviant lifestyle are turning up everywhere in NSW.

“You’ll never hear of a gay mardi gras or gay swimming carnival in Queensland.”

For Carswell, the papers confirmed that “a vicious and ideological government” had many ways to enforce its agenda.

“I was upset with what Joh’s government had done long before the papers were released,” he said.

“It used all government departments to stifle the AIDS council, it refused charitable status to the group, it enabled and encouraged police behaviour that went against good public health principles and it politicised the public servants responsible to do the same.

“It refused to provide funds, it refused to answer correspondence and it breached confidentiality, which just supercharged the race back into the closet and away from prevention, treatment and care.

“It confirms that what I knew was true, that the [Bjelke-Petersen government] did more than any other in Australia to victimise and blame gay men.”

Dr Wendell Rosevear was also involved with the epidemic from its earliest days and often faced the catastrophic consequences of the then-government’s ignorance and refusal to act.

“I remember those homophobic days well,” he said.

“Bjelke-Petersen said ‘there are no gays in Queensland’ and he was almost right as many guys would escape to Sydney to come out as it was too toxic in Queensland.

“There, without any family or peer support or knowledge of HIV and safe sex, they often took risks to ‘fit in’, only to get HIV and come home to say ‘Mum and Dad, I’ve got AIDS and I am gay’.

“I cared for guys dying at home whose parents didn’t even know, such was the secrecy and denial,” Rosevear continued.

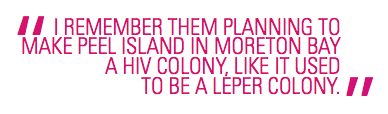

“I remember them planning to make Peel Island in Moreton Bay a HIV colony, like it used to be a leper colony.

“Our main role then was to provide palliative home care for guys dying at home as we had no anti-HIV drugs. It was popular for politicians to ‘gay bash’ and seek votes in AIDS fear while moralising. My learning teaches me that the most judgemental people usually have the most to hide.”

It was also common knowledge the state government once condoned police brutality of the LGBTI community.

“It wasn’t anything official, per se, it was always communicated through smoke and mirrors and passed down through the levels of the force,” said Jill Bolen, a former chief superintendent in Queensland Police who was outed as a lesbian during a 1977 “witch hunt”.

“When there were no sanctions against the homophobic behaviour of senior police officials, this of course gave permission to other officers that they could do anything they wanted.”

Many gay men also avoided seeking HIV tests and/or treatment for months, especially after police raided abortion clinics and had confidential information compromised.

“Those raids were just terrible, absolutely terrible,” Bolen recalled.

“The confidence of so many women was just utterly betrayed for political purposes. I had a friend involved in it and what I saw through them was so shocking.

“A lot of the men I knew who had contracted HIV wouldn’t open up about their status until they were very sick.

“The raids along with obviously everything that was going on in relation to how gay men were being treated by police and the government, of course contributed to preventing many men from seeking testing and treatment.”

The election of the Goss Labor government in 1989 and the subsequent decriminalisation of homosexuality a year later allowed for a closer relationship between QuAC and the state government. It also saw funding expansion for the organisation and the state’s response to the epidemic markedly improved to become consistent with the rest of the country.

While it may be almost 27 years since Bjelke-Petersen’s era came to an end in Queensland, for many who lived through it some of the residual effects from the state’s bleak initial response to HIV and AIDS still remains.

“This homophobia is still being felt today,” Carswell said.

“Both in the ignorance of some dwindling numbers of people in the general community and in terms of self-loathing and fear, even today, amongst modern members of the LGBTI community in Queensland.”

__________________________________

**This article was first published in the April edition of the Star Observer, which is available now. Click here to find out where you can grab a copy in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Canberra and select regional/coastal areas.

Read the April edition of the Star Observer in digital format:

__________________________________

It’s important to remember how oppressive the Joh government in Queensland was, and to realise that this oppression cost lives. It should also be noted that those of us living in Queensland were revisited by a doggedly anti-gay government recently under Newman and Springborg, and that the return of this homophobic mob remains a very real prospect. Newman/Springborg also refused to fund QuAC (and in fact stripped it of the funding it already had) and broke the partnership response to the epidemic which had served Australia so well, instead creating the Government HIV Foundation, which persists to this day. The sooner we get rid of the HIV Foundation and return to a fully-funded AIDS Council, the better off we will all be.