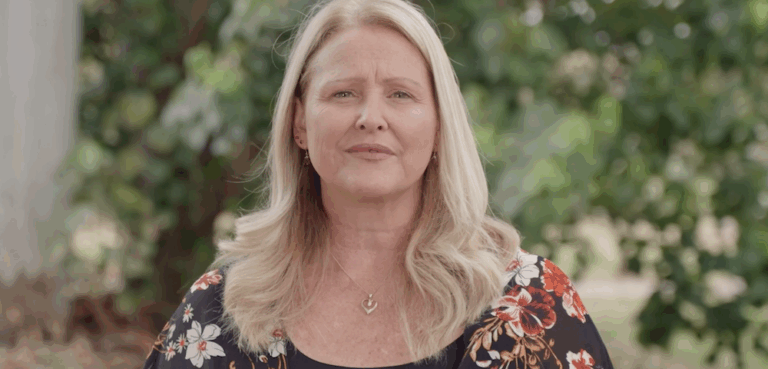

Closet Case: Michael Kirby

“I SHOULD have won an Oscar for my performances because I think I did a very good take on a straight man,” Michael Kirby says.

“I can still do it, if the needs arise.”

[showads ad=MREC]Since stepping down from the High Court in 2009, Australia’s longest serving judge has kept himself busy by, among other things, looking into human rights abuses in North Korea for the UN and working with organisations promoting LGBTI inclusion.

However, despite knowing he was gay from a young age, Kirby didn’t publicly reveal his sexuality until he was 61.

“I don’t believe I was ever positively deceptive, I simply wasn’t positively honest,” he says.

Homosexuality remained illegal in NSW until Kirby was well into his 40s.

“It’s hard for people to understand now the fear that having criminal laws targeted against you causes in the mind,” he recalls.

While he was studying at the University of Sydney in the 1950s, a particular figure of dread was NSW police commissioner Colin Delaney.

“He announced there was an epidemic of sexual perversion and formulated a crusade that meant even if you were not involved in any sexual activity — which I wasn’t — somebody might make an allegation against you even if was false,” he says.

Kirby remembers safety lay in silence: “It was a lonely time and I’m rather resentful of what was inflicted on me by my country and my society.”

Solace came from American academic Alfred Kinsey whose groundbreaking reports, published in the late 1940s and early 1950s, are credited with changing attitudes towards homosexuality.

“Following Kinsey’s investigations I knew that I was not alone, there was nothing wrong and it was simply a variation in nature,” Kirby says.

In 1969, when he was approaching “the ripe old age of 30”, he headed into a bar in Sydney’s Kings Cross and stumbled across the man who would become his life partner.

Before long, Johan van Vloten was invited to Sunday night dinner with the parents.

“It was a family tradition of ours that any of the children who wanted could come along to have sausages and mash,” Kirby says.

“So he was brought along and he kept coming year after year, decade after decade.”

By this time, most of Kirby’s family knew about his sexuality. But there was one person in particular with which the topic hadn’t been broached.

“I didn’t verbalise it with my mother until she was dying and I felt uncomfortable of severing that bind without having been totally honest to her,” Kirby recalls.

“So I told her, just before she died, and she looked at me and said, ‘Michael, I didn’t come down in the last shower’.

“‘You’ve been bringing Johan to Sunday dinner for the last 30 years, do you think I was blind?’”

In public though, Kirby continued to remain discreet. While known in various circles, being too “in your face,” he says, would have precluded him from high judicial office.

“Fundamentally it was a trick of the mind,” he Kirby says.

“So long as you don’t make us, the majority, face the awful reality that you exist, we will play along with this game and we will recognise your talents.

“But if you confront us with your actuality, that is breaking the rules and we will break you.”

Ultimately, it was van Vloten who gave Kirby the final push to go public, saying they owed it to the next generation to be open.

With much negotiation, yet with little fanfare, the publishers of Who’s Who — the encyclopaedia of the influential — agreed to record Van Vloten as Kirby’s partner in their 1999 edition.

“It wasn’t noticed for a while, and when it was one of the newspapers said ‘the non-secret is out’,” Kirby says.

“There was an attack by one columnist and by a senator but on the whole the world went on.

“The trains continued to run on time, or not on time, and people got over it. They had a lie down and they felt better the next day.”

He was surrounded by love but his work with a number of LGBTI organisations, including the Pinnacle and Kaleidoscope foundations, has shown him that not every gay person is so lucky.

“It would be good if everybody did come out and we lived in a society where that would be accepted as easily as left handedness and eventually we may get there,” Kirby says.

“But we’re not there yet and it’s therefore important that people should face the realities of the challenge that a lot of young people face in coming out and be understanding, kind and supportive.”

______________

**This article was first published in the September edition of the Star Observer, which is available to read in digital flip-book format. To obtain a physical copy, click here to find out where you can grab one in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Canberra and select regional/coastal areas.

Read our previous instalments of “Closet Case”:

Kerryn Phelps & Jackie Stricker

[showads ad=FOOT]