Taking a stand in the stands

“I WAS scared to death,” Jason Tuazon–McCheyne says.

“I’d never felt so nervous in my entire life.

“But because I was there with my family I had to do something.”

It was four years ago and Tuazon–McCheyne was in the stands at Melbourne’s Etihad stadium. Around him supporters were barracking for their side while throwing the odd barb at the opposing team. Most of the jibes were harmless enough, the boisterousness of the bleachers.

But some began landing far too close to home.

“The guy behind started shouting ‘poof’ and ‘faggot’,” Tuazon–McCheyne recalls.

“And then his daughter started saying the same things.

“It was awful and I didn’t want to have this going on so I turned around.”

Tuazon–McCheyne confronted the spectator and told him that, being gay, he didn’t appreciate the language being used.

Thankfully, the foul-mouthed fan was shamed into stopping but, unwilling to expose his family to the spectator in the future, he felt compelled to change his seats the following season.

It wasn’t the only time Tuazon–McCheyne — a marriage celebrant and the founder of the Australian Equality Party — has struggled to marry his lifelong support of AFL club Essendon with his sexuality.

“I remember one day an Essendon player said that AFL wasn’t a place where gay people are welcome, and it just broke my heart,” he says.

In an effort to make the footy a place that anyone — regardless of their sexuality — can enjoy the game, Tuazon–McCheyne established the Purple Bombers.

Launched in March, the LGBTI supporters group now boasts 70 members and has received high-profile endorsement from Essendon management.

However, new research released last month shows Australian sports still have some way to go to stamp out discrimination.

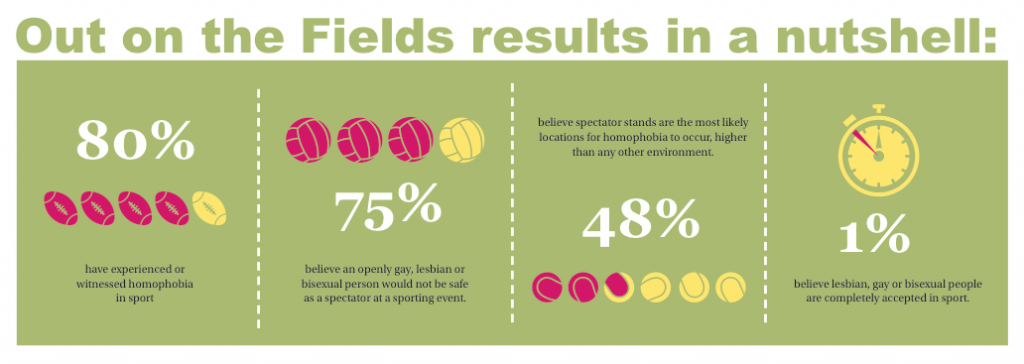

The Out on the Fields survey canvassed 10,000 people — gay and straight — finding 80 per cent had witnessed or directly experienced homophobia in sport.

“Is it only 80 per cent?” says Jacqueline Meredith, a soccer player from the south-western outskirts of Sydney.

“I’m surprised it’s so low, I would have thought everyone playing sport would have experienced some homophobia.”

She says the local club she currently plays for in Camden are supportive and teammates will openly admonish opposing players if they hear homophobia.

But her experience with other teams hasn’t been so rosy.

“In one of our games a player got sent off and one of the other players called her a ‘fucking dyke’ right in the middle of the game,” Meridith recalls.

“It made me scared to be myself.

“What would they say to me if they actually knew I was gay?”

Meredith says the stands can be a hotspot for homophobia and are somewhere she doesn’t feel she can be herself.

There’s good reason to be wary with the Out on the Fields research revealing gay people fear homophobia in the terraces above all other sporting environments, while 75 per cent of Australians believe an openly-gay person would not be safe in the stands.

The survey did not look at trans* participation, with the organisers saying they were focused on homophobia but hoped the results would spur further research into sport’s overall inclusiveness.

“It’s only a relatively safe space for gay people because we can hide who we are,” says Tuazon–McCheyne, highlighting he recently accompanied a trans* friend to the game who was too scared to go on their own.

“But you won’t find me putting my arms around my husband — unless of course we get a goal and everyone does.

“But I certainly wouldn’t kiss him to say hello. I don’t know any gay person who does that at the footy.”

Andrew Purchas, the head of the organising committee for the 2014 Bingham Cup Sydney gay rugby union world tournament — a principal backer of the survey – says the results are both alarming and worse than expected.

Meanwhile, Victoria University’s Dr Grant O’Sullivan says concerns about being accepted discourage lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people from sport, consequently missing out on the physical, mental and social benefits being part of a team can bring.

“The interesting thing about the stands is it’s where sports meets community and culture but [homophobia] spreads the message that LGB people are not welcome and it can put people off,” he says.

Yet some have suggested those who report homophobic incidents need to essentially just toughen up a bit.

In March, ACT Brumbies player David Pocock copped criticism after reporting the NSW Waratahs’ Jacques Potgieter for calling another player a “faggott” during a televised match.

And late last year, Collingwood club great Mick McGuane asked on radio station RSN why player Heritier Lumumba would “question the culture of the footy club” after the defender alerted bosses to homophobic graffiti in the changing rooms.

However, the argument that casual homophobia in the stands — such as the widespread use of the word “gay” as an insult — should be brushed off as heat-of-the-moment hubris is rubbished by O’Sullivan.

“The insinuation may be that ‘gay’ isn’t homophobic but it says you’re not welcome in this environment and that keeps people closeted,” he says.

In April 2014, the AFL, NRL, Australian Rugby Union, Football Federation Australia and Cricket Australia all signed up to the Bingham Cup-championed Anti-Homophobia and Inclusion Framework.

Indeed, the codes do seem to be taking homophobia more seriously.

Witness the difference between 2013, when the Newcastle Knights’ Ryan Stig said gay marriage was “demonic”, and a remark in April from South Sydney’s Isaac Luke who said goading fans from a rival team were “lil [sic] poofters”. The former was punished by the NRL with little more than a slap on the wrist; the latter with a $10,000 fine and an anti-discrimination training program.

While in April, reports of homophobic remarks in the stands led to a Western Bulldogs fan being evicted from the MCG.

It was possibly the first time in Australia that an anti-gay slur had been dealt with in such a way.

On a more local level, initiatives such as Play by the Rules are providing community sporting teams with advice and information to help them become more inclusive.

However, Meredith says she has never seen even a poster in a local club promoting LGBTI inclusion.

The Out on the Fields report recommends sporting organisations take a zero tolerance approach to fans and players using homophobic slurs, chants or humour — a stand O’Sullivan backs.

“It sends the message that this stuff will be acknowledged and picked up,” he says.

But it’s not happening yet, with Tuazon–McCheyne saying a friend was “harassed out of the stadium” just weeks ago, unable to bear the anti-gay language.

The AFL tell the Star Observer they are a leader in tackling discrimination with sexuality part of its anti-vilification policy since 2009. In addition, the league says they have put in place anti-discrimination training for staff and players, publicly backed anti-homophobia campaigns and have a presence at Melbourne’s LGBTI Midsumma festival.

However, they acknowledge there is still some way to go.

“In the same way that the fight against racism doesn’t stop with one education program, the AFL recognises that we can always build on and improve the programs and outreach to enable change,” a spokesperson says.

Purchas says shifting the culture of the stands will take time.

“There is a significant issue to changing what’s happening in the stands and it’s not going to happen overnight,” he says.

“But it is part of the journey to making sport more inclusive.”

_____________

**This story was first published in the June edition of the Star Observer, which is available to read in digital flip-book format. To obtain a physical copy, click here to find out where you can grab one in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Canberra and select regional/coastal areas.