‘Protest and boycotts against anti-LGBTIQ+ laws in Brunei will only go so far’

Brunei was recently met with international outrage after introducing the death penalty for gay sex, but writer Idris Martin believes that protests and boycotts will only go so far.

***

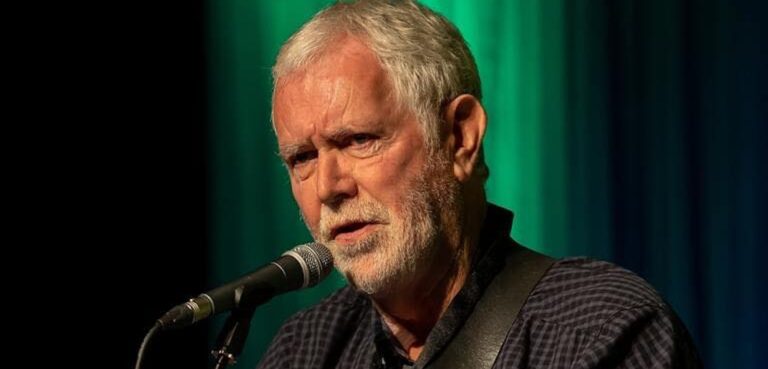

Last month, activists gathered outside the Royal on the Park Hotel in Brisbane to protest the persecution of LGBTIQ+ citizens in Brunei, following the implementation of a new Syariah Penal Code.

The code established capital punishments for a host of criminal acts, including adultery and sodomy, meaning being stoned is now a prospect queer-identifying people face in Brunei.

While the evidence threshold for such “crimes” is high and the Brunei government insist a conviction is unlikely under the new laws, the fear of prosecution is hugely damaging itself and inevitably someone will be prosecuted.

The code was first proposed in 2013 to address the gaps in the Brunei legal system, but international outcry saw Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah, the leader of Brunei, delay its implementation.

Since 2013, celebrities and activists have periodically renewed calls to boycott the Sultan’s investments, with the campaign now reaching Australia in light of the code’s recent enaction.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison joined the international condemnation of Brunei’s new Penal Code, while Australian companies and organisations like Virgin Australia followed suit by severing ties with entities owned by the Sultan’s investment fund; the Brisbane hotel was targeted due to its ownership by the Brunei Investment Agency on behalf of the Sultan.

These protests, however, seemed to have missed the mark. The Sultan has remained adamant about the implementation of the code and has said he wants to see Islamic teachings grow stronger in Brunei.

Brunei has been a Malay-Muslim Sultanate since the 14th century, with the Sultan seen to have a divine mandate to govern, and political power originating from that divine mandate.

In the 19th century, Brunei succumbed to European colonialism and a British ‘Resident’ was soon established in the Sultan’s court to essentially rule by proxy as was common through the Empire at the time.

Under British rule, reverence for the Sultans was amplified as Malay custom, to help combat possible dissatisfaction with the colonial presence in Brunei, and a penal code was implemented to civilise Malays.

This lead to the introduction of sodomy as a criminal act.

When Brunei gained independence in 1984, a constitution that maintained the esteem and prestige of the Sultan was implemented.

Malay-Muslim nationalism that developed during this period corresponds with the dominant narratives surrounding the Malay Sultans, with the Sultans coming to represent Malay traditions and being the guardians of Malay-Muslim culture.

Malay-Muslim nationalism birthed the concept of Malayness in the Malay world, built on three pillars of Malay language, customs and Islam. In a post-colonial world, Malayness is conceived not just as a measure of identity, but a rejection of colonial rule and assertion of Malay sovereignty.

In Brunei, the development of democracy ended with the suppression of the Brunei Revolt in 1962 by British and Malay monarchist forces, and the pillars of Malayness were codified into the national philosophy of Malay Islamic Monarchy.

Under this philosophy, not only is the Sultan’s right to absolute authority confirmed but it perpetuates the conflation between Malayness, Islam and the Sultan’s reign. And his reign has seen the accumulation of massive personal wealth.

The Sultan’s personal assets are incorporated into the state-owned Brunei Investment Agency, which further manages the General Reserve Fund of the government and its assets.

It seems an unlikely coincidence that the national philosophy of Brunei proclaims this substantial wealth and power as the Sultan’s right, due to his status as leader of Islam and the Malays of Brunei.

Under the doctrine of Malay Islamic Monarchy, the intertwining of Malayness, Islam and reverence for the Monarch means that when the Sultan declares he’d like to see a greater embrace of Islamic teachings in Brunei, he means a greater understanding of Islam that confirms his divine right to be Sultan. (His divine right to obscene wealth and absolute power.)

That is not to say that the Sultan does not enjoy popular support in Brunei – the national narrative of defiant Malayness in the face of colonial powers is a compelling one.

But the Sultan himself has expressed concerns about the influence of globalisation, particularly upon the wealthy and well-educated population of Brunei.

It’s not hard to see the threat to his position any sort of democratic movement would pose.

And it’s those who deviate from the norm that seem to embody this threat: Women, LGBTIQ+ people, the poor – the new Syariah Penal Code is wide-reaching in its brutality.

Solidarity and action is essential to combating this regression, yet campaigns that see the repeal of the new Syariah Penal Code as the goal are missing what needs to change in Brunei.

Not only is it incredibly unlikely that the Sultan is going to repeal the violent measures of the new Syariah Penal Code and decriminalise homosexuality, but so long as Malayness is identified with an Islamic Monarchy there is little room for progress.

Instead, Australians should focus our efforts on supporting progressive Malay activists and amplifying their voices.

It is only through their efforts that narratives of Malayness can evolve to include all Malays for who they are, unattached to arbitrary tests of faith and cultural loyalty.

Efforts which best demonstrate that progress and freedom are not Western ideas, alien to Malay culture, but things Brunei must embrace.

And freedom is not a commodity the Sultan can afford.