Belfast Pride held against backdrop of ongoing division in Northern Ireland

Belfast Pride was held in 2018 against a background of ongoing division and political paralysis in Northern Ireland.

The main political parties–representing the two divided and still largely segregated communities–are refusing to work with each other. There has been no government for 18 months, and Westminster is refusing to step in.

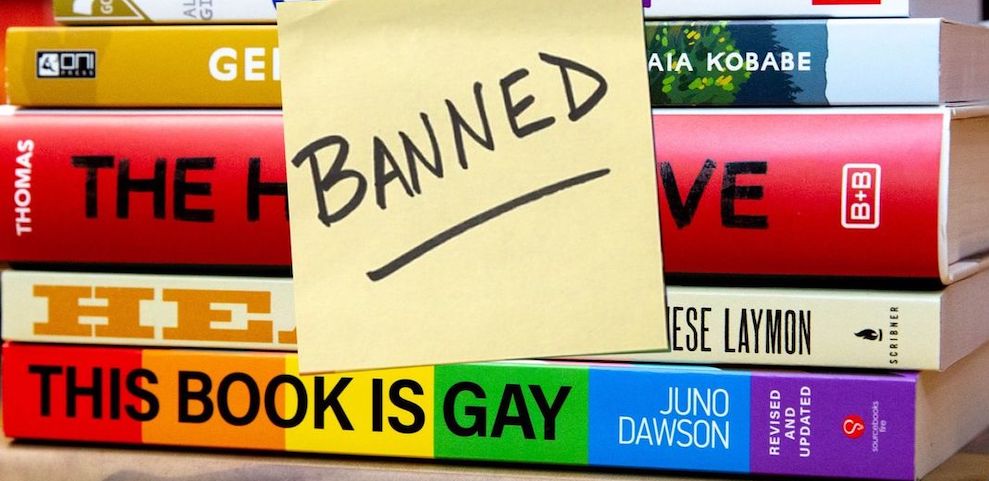

Three issues represent a red line for the two sides. Two of those issues are of core concern to the LGBTI communities of Northern Ireland—the extension of marriage equality and reproduction rights (i.e. the right to abortion).

Belfast Pride however brings people of all sides together in the largest cross communal event in the province. In doing so, it presents a conflict free zone, offering the hope of how a normalised society can look and feel like.

In Belfast, Pride explodes over a conflicted society; more as dazzling fireworks than incendiary bombs. Once a year, the LGBTI communities, joined by thousands of family, friends, and supporters, find each other, despite an eternal divide, to create one joyous manifestation of shared experiences and easy camaraderie.

Troubles and Terrors

In Northern Ireland, there is currently no active government, while the “authorities” (read bureaucracies, NGOs, and academics) understand Belfast in terms of a “post-conflict society”. However, terms in Northern Ireland conceal many harsher realities. Euphemisms have always given comfort to those trying to comprehend and manage Northern Ireland.

No matter what term anyone uses, Northern Ireland remains a deeply conflicted society.

It is twenty years since the Good Friday Agreement. This marked the formal end of a horrific, internecine war between Republicans and Unionists. It was a war of frightening familiarity; pitting neighbourhood against neighbourhood. There was no in-between and nowhere to hide. It was a war that was fought to exhaustion.

These were no mere troubles; they were the terrors.

With a small change of thinking, the first Good Friday offered a hope for a brighter future. But since then, there has been precious little progress toward real communal reconciliation. Education is still 90 per cent segregated and “mixed marriages” between members of different communities remain the exception.

Ironically, the Good Friday Agreement fundamentally institutionalises sectarianism. It is a politicians’ agreement, not a people’s peace. Without more fresh thinking, Northern Ireland will remain a fractured and unhealable society. History’s breath will continue to brood close as the cool, damp sea air; and the future will remain predictably contestable.

Storms and rainbows

However, despite this bleak forecast, Pride offers more than a heart-warming rainbow after a never ending storm. Pride is actually Northern Ireland’s largest cross communal event and serves as a balm for a divided and damaged city.

It draws in thousands of people from across Northern Ireland and beyond to the city centre—way beyond its natural demographic; all keen to share in its open-hearted expansiveness. Sadly, after a shinning, shimmering weekend, it retreats, leaving a teasing chimera for a better life.

Broadly, LGBTI people in Northern Ireland are free to live out their lifestyles as freely and expressively as anyone else in the socially evolved world. An anti-Pride demonstration failed to attract enough badly-suited people to fill two telephone booths. With just one on hand, they were forced to spill out onto the street.

However, the LGBTI people of Northern Ireland still have two political struggles to win; the extension of marriage equality and the right to abortion; both to the same levels accorded in both the UK and the Republic.

Sadly, both issues have been sucked into the ever hovering, grasping, and unforgiving sectarian vortex. They now constitute two of the three “red-line” issues which the two power-sharing parties say they wont budge on. So, without movement on these issues, neither party is willing to participate in a power sharing government.

A sweet way forward

In everyday life, most people have to declare which side of the sectarian divide they align with. Even if they don’t want to, a mark goes before them. The mention of a neighbourhood, school, a place of work, or even a first name comes with an assumed identity and an expected way of thinking, acting, and”p responding.

No-one is left out. The grim joke of having to declare as either a protestant atheist or catholic atheist is as sardonic as it is true. It doesn’t take long to find a mixed Greek Orthodox/Irish person who identifies as Protestant; or a gay Catholic Unionist. In the political sphere, there are even “Green-Greens” and “Orange-Green”, if you can get your head around that.

It is significant then, that at the personal level, one’s LGBTI identity is likely to trump the ever dominant and demanding communal identity. Such predetermined categories are of less significance to LGBTI people. They are more likely to have friends and partners from any number of backgrounds, even from beyond the binary. They are also more likely able to form truly “shared spaces” —another euphemism in the Northern Irish lexicon.

The votes in Australia and the Irish Republic were the loudest proxies possible for the continued expansion of open, tolerant and diverse societies. Similarly high opinon polls in Northern Ireland suggests there is an unmet yearning such a future.

Clearly, many people despair with living in such a reductively binary world. It grinds everyone down, narrows their opportunities and corrodes their relationships.

It’s no wonder that once a year, people who want so much more from a “post-conflict peace” so readily embrace Pride, as it expands over the city. Thousands flock to the city centre as it refreshingly courses through the bulging city streets, pushing out the stale tensions; eradicating the visible and invisible scars and barriers.

For Belfast, Pride offers its people a sweet taste of what life in a normal society can feel like and look like; one where the leadened labels of the past are no longer currency.

As long as humans are indeed human, people yearning for better lives, will always find ways to defy political imperatives to live within such soul-destroying constructs.

And when marriage equality is achieved in Northern Ireland, the current abysmal rates of mixed marriages will surly improve as couples, less concerned with the background of the other half, are finally represented in the official statistics.

In a Zone of Conflict: Belfast Does Pride from PhotoTeam on Vimeo.

The tribalism which has remained a part of Northern Irish politics is the problem, both tribes are rooted in homophobic religious tradition.

Yet the British Conservatives under David Cameron (and also Adelaide-born Lynton Crosby as Tory campaign director, influenced by John Key the NZ centre-right PM who got marriage equality through the NZ parliament in the same way Turnbull couldn’t here) and the Republican Irish via constitutional reform (they won in a canter) whom both sides of Nothern Irish politics look to both are well ahead of Australia in the marriage equality issue.

Northern Irish politicians are disgusting. They are unfit to represent the Nothern Irish people who are (mostly) wonderful.