Cumberland Council’s Book Ban Has Been Overturned, But What is Really Happening in Australian Libraries?

By Lisa Given and Sarah Polkinghorne

This story about the Cumberland book ban originally appeared on The Conversation Australia.

At Cumberland City Council in the western suburbs of Sydney, one man – Councillor Steve Christou – persuaded the council to ban books about same-sex parenting from the council’s libraries.

The change was short-lived. People fought back. More than 40,000 signed a petition to lift the ban.

Only two weeks later, the Cumberland Council reversed its decision, voting decisively (13-2), following impassioned pleas by residents, and with many people protesting on the streets.

My story on what happened in Cumberland last night

– Pro-ban Labor councillor voted to overturn the ban

– Labor councillor who walked out voted to overturn

– An independent who said hours before the meeting he’d vote to overturn…but then voted pro-banhttps://t.co/3gTWSmKia6— Leonardo Puglisi (@Leo_Puglisi6) May 15, 2024

Librarians under attack

Librarians are leaders in the fight against book bans. They have faced significant backlash for their efforts. Australian Library and Information Association CEO Cathie Warburton has reported that

people are going into libraries, grabbing books off the shelves, reading them out loud and saying “These shouldn’t be here”, calling librarians horrible names and threatening doxxing and physical violence. It’s incredibly distressing.

Book banning efforts are often highly coordinated. People distribute lists of books that may (or may not) be in the collections of their local libraries. These culture-war attacks on libraries and librarians are often motivated by grievances against progress, such as LGBTQ+ visibility and acceptance, and other forms of diversity.

But they are also part of a wider reactionary movement. The issues extend beyond the specific content of individual books. Calls for book bans are evidence of a broader moral panic that presents a real danger to individuals and society at large.

Libraries and librarians are common targets because they are easy for the public to access, and because they represent (and foster) learning, ideas, imagination, equality, choice and barrier-free access to information for all.

Would-be book banners have very rarely read the books they challenge. When books are read, they are far less likely to be banned.

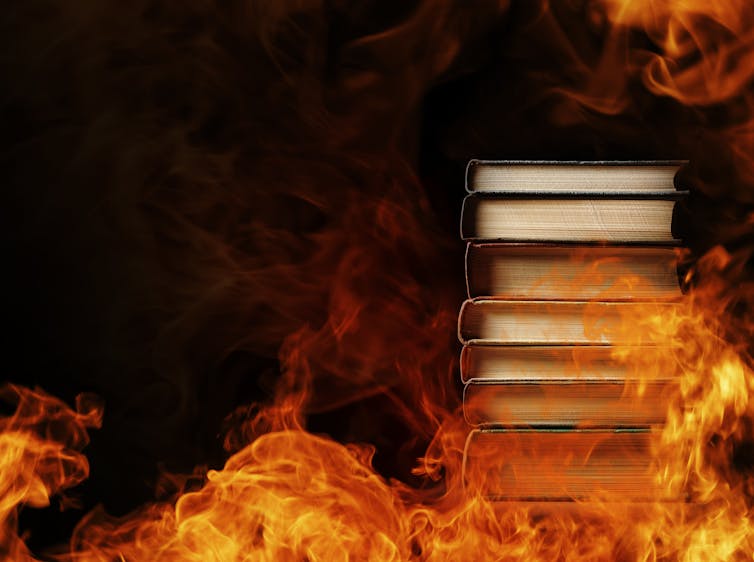

Histories of censorship

The Cumberland episode is only the latest in the global struggle for freedom of information access. Such censorship dates back at least as far as Shakespeare. The first American book ban occurred in 1637, when Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan was suppressed for its criticisms of Puritanism.

The issue remains highly contentious in the United States. PEN America’s latest report shows a 33% rise in the number of book challenges in US public schools, with almost 6,000 instances of books banned since 2021.

The Alabama House of Representatives recently passed Bill HB385. If it passes the Senate, the bill will override libraries’ book challenge policies. Librarians would have seven days to remove contentious material or face criminal penalties.

Australia also has a long history of censorship. Many titles we now consider “classics” faced bans, including Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, James Baldwin’s Another Country and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. As literary historian Nicole Moore documented, it was once “routine to have your suitcase searched [for obscene materials] on the way into Australia from another country”.

More recently, in March 2023, Maia Kobabe’s award-winning memoir Gender Queer was removed from a Queensland library, and faced many other challenges, globally. Bernard Gaynor, the conservative Catholic activist who led the call to ban the book, is taking the Minister for Communication and the Australian Classification Review Board to the Federal Court of Australia. The decision will come later this year.

Censorship remains a local – and global – concern.

Information access for all

Professional librarians have battled these kinds of challenges for decades. The American Library Association, founded in 1876, issued its first anti-censorship notice in 1939, in response to Nazi book burning and other international attempts to suppress information.

In 1953, the American Library Association issued their Freedom to Read statement, with ongoing support for libraries challenging book bans across the United States.

In a joint statement, the Australian Library and Information Association and the Australian Public Library Alliance explain that libraries “defend equity of access to information” and “cater for all members of the library community”.

This position reflects global standards for information access upheld by libraries worldwide. It includes the key principle that the “perception that material may offend or cause controversy to a person or a group of people is not, of itself, a reason to limit purchase or provision of an item containing that material”.

The International Federation of Library Associations states that censorship “runs counter to Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”. Libraries are expected to:

- provide collections and services that are free of intentional censorship

- base decisions on professional considerations (e.g., quality, currency, format, cost, etc.), rather than limiting based on political or religious considerations or cultural prejudice

- educate people on issues of censorship and encourage them to practise freedom of expression and freedom of access to information

- advocate for removal of censorship restrictions affecting libraries and society at large.

Policies and procedures

Librarians do more than handle attempts to ban books. They develop policies and procedures designed to ensure free access to information, for everyone. They are expert professionals, whose jobs often require difficult selection decisions and challenging conversations with angry or offended community members.

Libraries already have established processes to handle removal requests. They apply guidance from professional associations, including resources like the Selection & Reconsideration Policy Toolkit for Public, School, & Academic Libraries.

Requests to remove materials often start with informal conversations to address concerns and educate complainants about the library’s mandate for equitable access based on the whole community’s needs and interests. A formal process often requires a written submission. Library staff will then reconsider the book in light of the library’s collection policy.

Removing books from a collection does happen, as librarians must ensure the collection remains useful and relevant. Libraries routinely consult with community members and seek feedback to ensure collections match community needs. They also review materials to ensure outdated works (for example, older editions) are replaced with texts that include current information.

These are some of the routine, behind-the-scenes tasks, which collections librarian Scarlet Galvan explains are critical to ensure “collections are for use, not reinforcing assumptions”.

Massive pro and anti-book ban rallies outside Cumberland Council tonight pic.twitter.com/4hudN9MDUo

— Alex McKinnon (@mckinnon_a) May 15, 2024

The need for community involvement

Librarians rely on individuals and communities to stand up and oppose censorship, as residents did in Cumberland. Vocal community and government support for libraries is critical to battling book bans. Many other professions, such as journalism and teaching, also play critical roles in documenting censorship and countering book challenges.

So how can you help? By signing petitions, speaking up at council meetings, volunteering to serve on a library board, voting for candidates who support libraries, and borrowing books about diverse families to ensure they have a circulation record of being used and valued.

As the outcry over the short-lived Cumberland City Council ban shows, everyday Australians value libraries and the information they provide to their communities. Public support is needed to defend against future attacks and to send a message to governments that banning books is not acceptable.