There was a dark time in Australia’s recent history when same-sex attracted men were assaulted and killed while cruising for sex at beats at an alarming rate. And while many perpetrators were convicted and sentenced, a handful of cases remain unresolved to this day. Matthew Wade revisited the murders and spoke to those who were closely tied to them.

It was night.

The jovial banter between eight teenage boys pierced Sydney’s summer air like a cast of falcons. They were shooting hoops on an inner-city basketball court.

When the air grew stale, one member suggested they visit the public toilet in Alexandria Park to find a telephone number that had been crudely scrawled on one of the cubicle walls – gay men looking for discreet sex were easy prey.

A phone was dialled, the call was answered.

And like clockwork, as Richard Johnson parked his car nearby and walked over to the toilet block in search of his mystery hook-up, the group of teenage boys ran towards him and knocked him to the ground with one blow.

The boys, now known as the Alexandria Eight, then took turns punching and kicking his head and body until he was left fatally wounded on the ground.

It was 1990, and when interviewed by detectives the following month and asked why the attack was carried out, the eldest of the boys simply replied: “because he was a fag.”

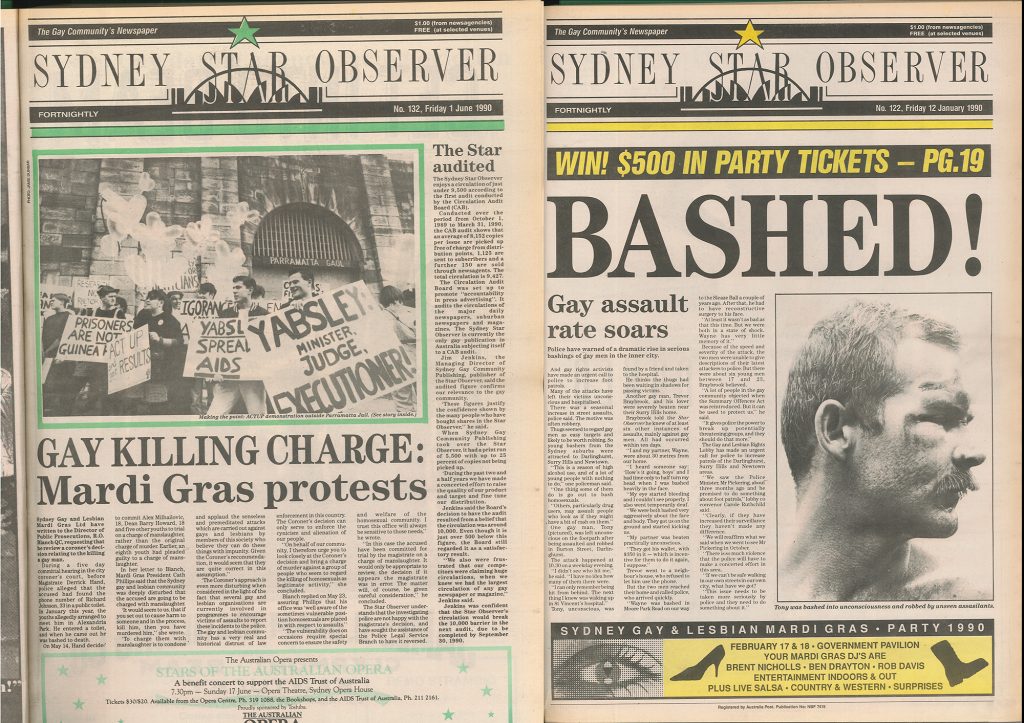

Between 1989 and 1999 there were 46 known gay hate murders that took place in New South Wales, with an additional 30 that remained unsolved and have only been revisited in recent years.

Assaults were even more frequent, with 1990 seeing 38 gay-related beatings reported to the Surry Hills and Kings Cross police in one month alone.

Same-sex attracted men were hunted by bigots as sport.

They were mainly carried out at beats in places like Bondi and Tamarama. Beats provided an ideal site for the violent perpetrators: they were secluded, they were often frequented after the sun had set, and they had a magnetic pull for many same-sex attracted and curious men.

Opening a queer rag and reading an article about a gay hate crime became commonplace, a morbid signifier of the increasingly dangerous times gay men and lesbian women were living in. And each new case was no easier to digest.

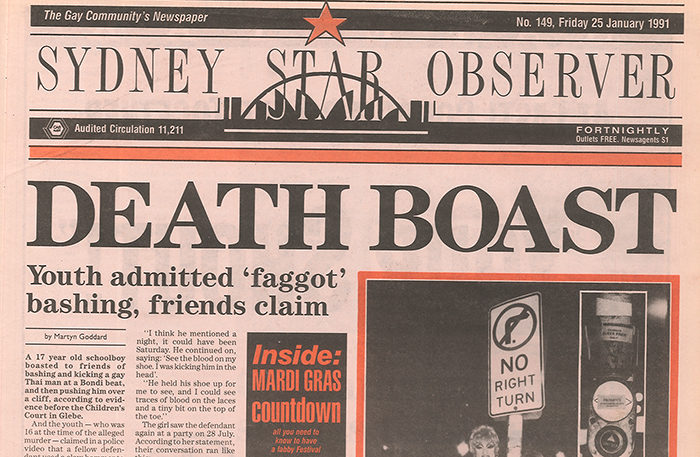

Thai student Kritchikorn Rattanajaturathaporn was found wedged in the rocks at the bottom of a sea cliff at South Bondi.

John Russell was similarly found dead in a rock pool at the bottom of a 12 metre cliff at Bondi Beach, a popular beat at the time.

And Garry Webster was found dead in a Campbelltown motel with the word “poof” cut into the bloodstained mattress.

Rattanajaturathaporn was murdered by the Tamarama Three, comprising brothers David and Sean and their friend Matthew, who were all sentenced to twenty years in prison.

A school friend of theirs made a statement at the committal hearing, saying one had boasted about what he’d done shortly after the crime.

“[The defendant] came up to me and said, ‘guess what? We beat up this slap [Asian],’” she said.

He continued on, saying “see the blood on my shoe – I was kicking him in the head.”

When Peter Rolfe discovered his missing partner Stephen’s car, empty and parked at a beat he used to frequent, he was mortified.

“Stephen used to do beats quite often and I used to do them with him, but it did surprise me he was murdered at one – he’d always been so fearless,” Rolfe told the Star Observer.

“After I’d discovered he was missing I was driving past Deep Creek Park and I remembered that Stephen used to go there, so I drove in to check.”

As soon as he found the car he phoned the police, who took Rolfe to the station before searching his house to make sure he hadn’t been keeping Stephen tied up somewhere himself.

For months Stephen’s body had vanished, until 21-year-old Richard Leonard stabbed a taxi driver at Collaroy Plateau, not far from the beat where Stephen had gone missing.

“The detective in charge was looking over into Deep Creek which you could see from there and he made a comment to his partner about that,” Rolfe said.

“Soon after a torso washed up at Pittwater, and through a DNA test they discovered it was Stephen, and that he’d been shot with a bow and arrow.”

Witnesses then came forward to tell police that Leonard used to hang around Deep Creek with a bow and arrow.

Leonard had fired an arrow into Stephen, killed him, dismembered his body, and kept it in a freezer for four months.

He then dumped the body parts into the sea.

Rolfe said finding his partner that way and being surrounded by so many assaults and murders at the time was horrifying.

“I was threatened at a beat in Collaroy in the early eighties,” he said.

“I was always very careful, you had to be careful.

“Five or six kids came in, led by a much older kid and I just told them to fuck off.”

Despite his partner’s case being resolved, and the perpetrator caught early on, Rolfe said he can’t express just how important it is now for the police to work on resolving the unsolved cases.

He currently runs a support group for homicide survivors called Support after Murder, through which he also does a lot of lobby work.

“We’ve been lobbying the NSW Police Force and the government to increase the rewards for unresolved homicides,” he said.

“It currently averages around $150,000 but we’re aiming to push them to $1 million.

“It’s very important… we just want to be able to pay anyone with information around the identities of the people who committed these murders.”

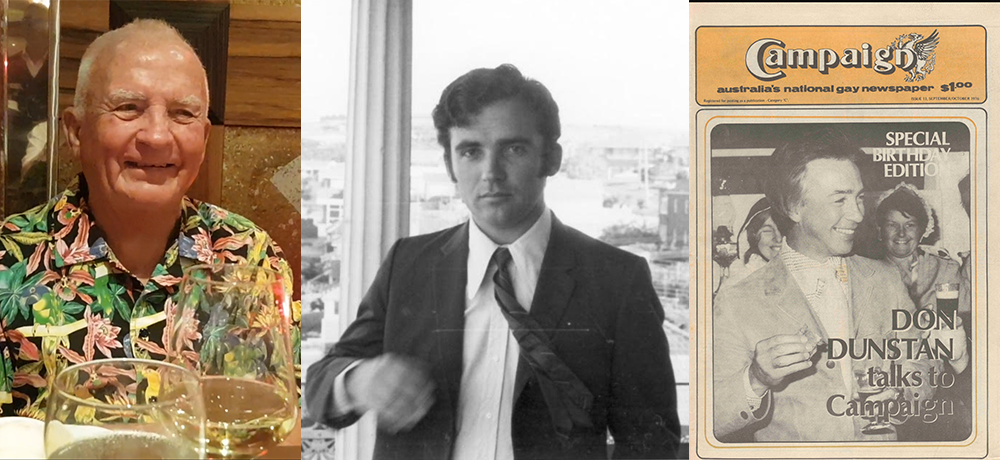

The beat murders had begun to amplify by the time Ulo Klemmer became a beat officer with ACON in 1988.

His role was to hand out condoms and chat with men that were cruising about sexual health and HIV at the beats around Western Sydney.

He said despite the gay hate murders becoming more prevalent at the time, there were still a number of people at risk who may have been unaware.

“Some people knew, and some people didn’t, it depended how attached to the community you were,” he said.

However, Klemmer said when it came to beats, an awareness of the risks or danger involved in cruising at night wouldn’t deter many same-sex attracted men from visiting.

“I think testosterone takes over at a beat, the worry goes out of it and the need [for sex] becomes more important than the worry,” he said.

“You take risks you wouldn’t normally take, it’s kind of dangerous.

“One of the conditions of our job was that we worked in pairs, because we were working day and night.”

As the nature of his job involved going from beat, to beat, to beat, Klemmer naturally had a small handful of dealings with the tragic murders that occurred.

The year that he started working as a beat officer, the body of Scott Johnson was found at the base of a cliff at Manly on Sydney’s northern beaches.

He had been completing his PhD, happily living with his partner in Sydney, and had made an amazing leap forward with his research that he was ready to tell his professor, whom he’d booked in a time to see.

The NSW Police ruled his death as a suicide.

“The sergeant with Manly Police at the time brought up that the area was a beat when we spoke about it, but publicly always denied any knowledge of it being a beat at the time,” Klemmer said.

“They dismissed it as a suicide.

“That’s why years later when I got a call from a U.S. investigator asking me if I’d put that knowledge in a statutory declaration, I did.”

A street watch violence monitoring project in undertaken by the Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby and Counselling Service found that children as young as ten were hunting in packs, and responsible for some of the assaults against gay men and lesbian women.

It found that in six per cent of beatings, the age of the attackers was between 10 and 15, and 43 per cent were carried out by people between 15 and 20.

It was the many beatings and murders perpetrated by young schoolchildren that motivated Sue Thompson to reach out to high schools in her role co-ordinating the gay and lesbian liaison program in the Sydney Police in the nineties.

Gay teacher Wayne Tonks was brutally murdered by two 16-year-old students from Cleveland Street High School, after he had received threats and school and had his house ransacked.

In response Thompson and the Sydney Police’s gay and lesbian liaison officers ran three full days of workshops at the school the students were from.

“I took in a panel of 20 gay and lesbian people and kids could ask questions,” she told the Star Observer.

“It was the first time anything like that had ever been done in a school, it was an incredibly huge step forward.

“It had only been six years since homosexuality was decriminalised in NSW so there was a lot of resistance to dealing with these issues… I’d always bring it down to violence, and say you’re encouraging a culture where violence is okay, where teenagers are picking on innocent gay men.”

Thompson does admit that huge changes have taken place since then, and she hopes justice will be brought to the many unresolved cases to ensure families and loved ones can be brought out of the dark they’ve been in for the past two decades.

“It’s incredibly important that justice has been done when the most injustice has been done,” she said.