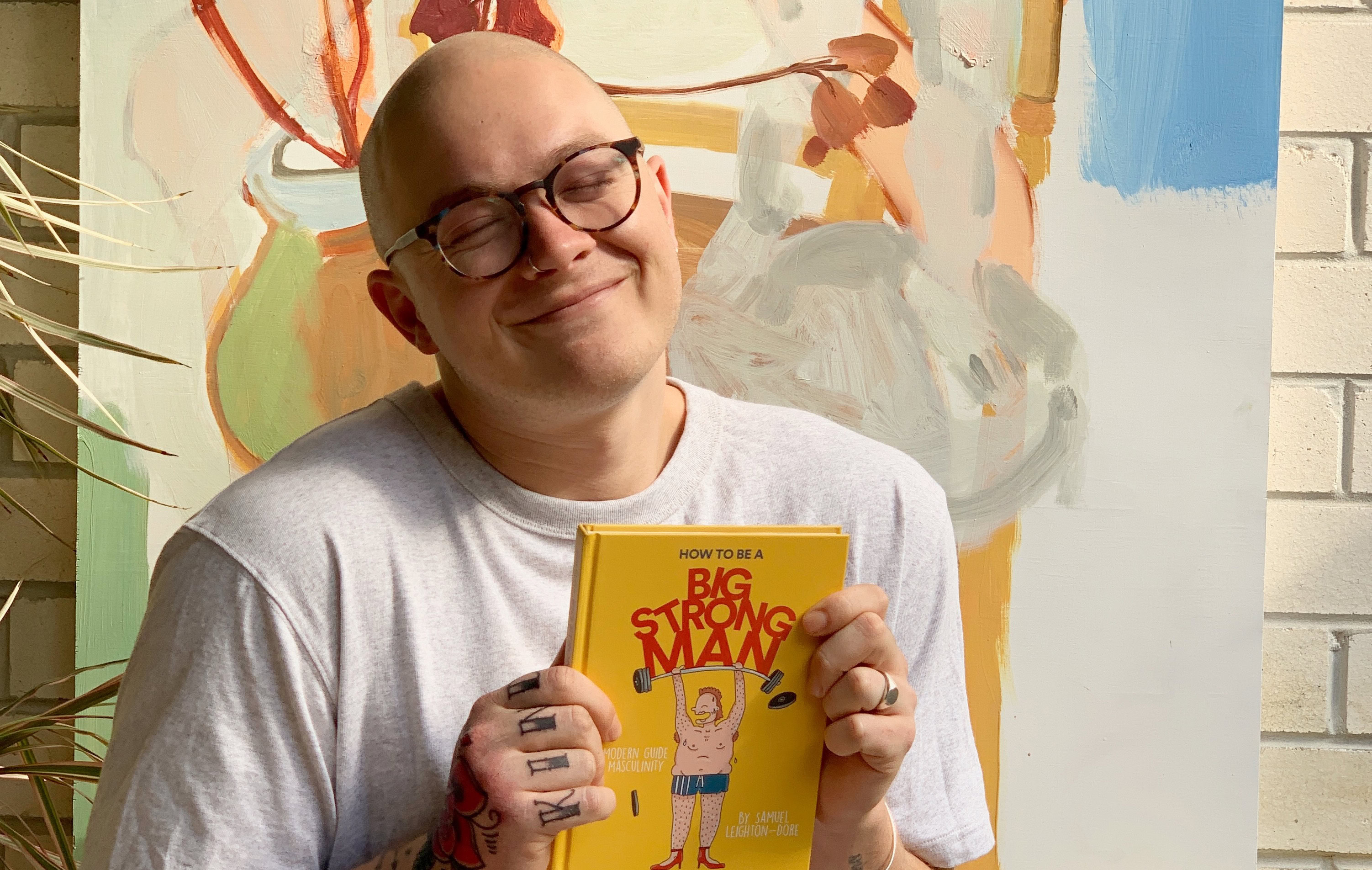

Samuel Leighton-Dore is stripping the toxicity from masculinity

In his new book How to Be a Big Strong Man, Samuel Leighton-Dore is trying to help liberate males from toxic masculinity through humour. He told Andrew M Potts that he doesn’t understand why so many people feel threatened by the idea of a world where men can be happy and express their emotions.

What was your original inspiration for putting this book together?

Earlier this year I got an apology via Facebook from one of the kids who used to beat me up in Year 7 when I was at an all boys high school. That was a low point for my life and I’ve had a few other messages like that over the years and that got me thinking about how a group of teenage boys could go from being so mean and hurtful and violent when I knew them to becoming reflective decent adults and what it was that caused them to behave in that pack mentality to begin with. That became my doorway into the topic of toxic masculinity.

Where do you think these expressions of toxic masculinity come from?

I was lucky to have a really sensitive father so I was always quite sensitive myself and able to express my emotions but that also made me a target. But for a lot of young men there’s shame attached to difficult feelings and expressions of sadness. I think when those feelings aren’t expressed at an early age they don’t disappear, they just bottle up until they’re expressed through anger later on. This project has really been a tool for me to learn about that and I’ve been learning as I go, reflecting on this. It’s been really valuable in that way. It’s been educational for me.

Did you feel that the bullying you experienced was homophobic in nature?

I’d always assumed that it had been homophobic and I’d always written it off as homophobia. But now that I reflect on it, I didn’t come out until I was sixteen and I wasn’t sexually active until after that so I think it couldn’t have really been homophobia. Looking back I think it must have been a reaction to the way I presented myself as a boy, which didn’t kind of fit their ideas of how a boy should be. This project has been one of reflecting on my upbringing and childhood and experiences with bullying, but taking my sexuality out of it and instead looking at myself and as a man and how I relate to other boys and men. It’s been kind of fascinating to take the gay goggles off for a moment and look at other ways that these problems manifest themselves in all types of men.

I’ve wondered whether expressions of homophobia by teenage boys might be a way for them to signal their heterosexual credentials in the absence of having had sex yet. Does that ring true for you?

I’m not sure how much boys that age really understand about sexuality and what these things entail in an adult sense so I think at that stage derogatory words are more used to isolate and to hurt and they come from a place of complete ignorance. I think when people are bullied at that age it’s often more just because they stand out in being different rather than an assumption that they are gay and there’s a real sense in high school of needing to not be at the bottom of the food chain. So being able to isolate or identify a weaker target is tempting for boys in high school and they pile on. And I wonder whether their need to do that stems from unhealthy emotional outlets in their own lives. If they don’t feel good enough in their own homes in the eyes of their father, if they’re experiencing being spoken down to, or demeaned for being emotional in the past then it would only make sense that they would enter high school and do the same to others. That’s the real theory behind this book and my work as an artist – if we can create a sense of flexibility around masculinity and around the language associated with it, the way we think about it will start to change, and when that starts to change then the way we show and express masculinity might become healthier.

This seems to be a theme that’s been running through your visual arts and your writing for a long time?

Yes. I’m so passionate about it and I think the reason for that is this subject has become more divisive than it needs to be and it drives me nuts that people are arguing about it. Because I’m not sure people properly grasp the nature of what these conversations about toxic masculinity are trying to achieve. Nobody is saying that masculinity in itself is problematic or inherently toxic. Nobody is trying to change any non-violent man. We’re not trying to force straight men to be gay. We’re not trying to force straight men to enjoy pop music or wear pink. We’re simply trying to remove the expectation that boys and men need to be a certain way from a young age so that they can make choices about how they express masculinity of their own accord. And when people are allowed to do that then they’re going to be healthier and happier. I don’t understand the us versus them mentality that seems to seep into this conversation.

What do you hope that people get out of this book and your body of artwork?

I really would love for my art to be a way to bridge this divide a bit and to show through humour and art that toxic masculinity isn’t a scary word and its not an accusation about males or a threat. It’s just about acknowledging where we’ve come from in the past as males and trying to hold our ideas of masculinity a little looser so that we all have room to move and grow.

If anything, there seems to be more benefit for straight men in terms of achieving a liberation from toxic masculinity?

Totally! I mean I can’t speak for women, and I know that women bare the brunt of toxic masculinity, but what I can speak to is that men are harmed greatly by it as well and and there really are no winners at the hands of an emotionally unhealthy man. They’re violent to and kill women and they’re violent to and kill other men and themselves. It’s kind of crazy that there is so much resistance to the idea that men should look after themselves emotionally. I find that really frustrating, yet intriguing at the same time. It really should just be a conversation about how to raise happier boys and make happier men and who doesn’t want men to be happy?

You’ve spoken about there being an inherent strength in vulnerability through your work. Could you explain what you mean by that?

Throughout history, masculinity has been presented as kind of a stoicism. If you look at historical statues of men and the paintings and depictions of men it’s always these emotionless unsmiling stoic figures. But I think a lot of those men died young and unhappy. So I think there is a unique strength in vulnerability. It shows that you have a sturdy emotional foundation within yourself that allows you to be vulnerable and that is more lasting than physical prowess or a capacity for violence. I would argue that an ability to be vulnerable takes a lot more guts and courage and I think guts and courage say more about strength than than an ability to suppress emotions successfully or lash out violently, because anyone can do that.

How To Be A Big Strong Man is out now from Simon & Schuster