What’s past is prologue

WARNING: this article contains material some readers may find distressing.

OVER a period of three to four months in 1977 Tom Anderson was sexually abused by his employer, a man in his 40s. Tom was 14 years old.

“Through that whole process I had no idea of actually what was going on. I was so naïve. I was groomed by a paedophile who made me feel like a man when I was 14. He made me feel important. He praised me, heaped attention on me, gave me porn,” Tom said.

“It was our secret. It was between men.”

The abuse ended when Tom received a phone call from his employer at his house, asking him to play golf the next day. When Tom hung up the phone he went to his mother and told her he had been sexually abused for the past four months.

Tom’s mother took him to the police station where local police conducted a preliminary interview, before officers advised his parents they didn’t need to be present for further interviews. Tom said a lawyer was never mentioned.

He was interviewed for a further three to four hours, before being driven by police from Greensborough station to police headquarters in Melbourne CBD. There, Tom remembers being examined by a police surgeon, who examined his anus for evidence of semen.

Neither he nor his parents became aware that he was being charged with an offence until towards the end of the interview process. As he had engaged twice in an act of sexual penetration by his abuser, Tom was charged with buggery.

He remembers his mother telling him she thought the police officers were just doing their job, continuing to believe they had done the right thing by going to them.

“We went to the police because the police were the system. The police were there to protect us,” Tom said.

“The system let me down. The system I always thought was there to protect me was the system that abused me.”

Tom had to go to the Victorian Children’s Court and plead guilty before a magistrate. He said he was told to admit he had done the wrong thing, despite not understanding at the time what the charges meant.

He received a 12-month good behaviour bond with no conviction recorded, provided he didn’t have sex for the following 12 months.

His abuser was also charged, and pleaded guilty.

“It took me a long time to realise I’d done nothing wrong. It took me 28 years to realise that I did nothing wrong,” Tom said.

“It took me another 10 years until I started to actually believe it.”

On the night of his 40th birthday, Tom’s mother spoke to him about what had happened for the first time. She apologised, and told him the greatest mistake she believed she had ever made as a parent was not taking her son to counselling after the ordeal was over. She told him the police had advised her it wasn’t necessary, because Tom would eventually forget about it.

Until that night and that conversation with his mother, Tom had borne the burden of his abuse at the hands of his employer and the state completely alone.

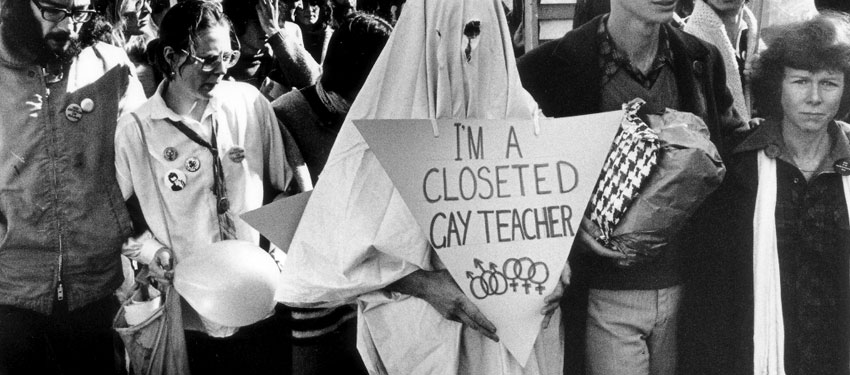

A few years after his 40th, he told his story to human rights lawyer Jamie Gardiner, who had been central to the campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in Victoria. The activists who led the campaign achieved their aims in early 1981, where the law Tom had been convicted under was no longer in effect.

Gardiner told Tom the story epitomised the injustices they had been fighting against. He said police would have had discretion over whether to charge him, and they didn’t have to do what they did. He said Tom had been the victim of both an unjust law and the entrenched homophobia of the time.

This was the first time Tom had considered he might not have done anything wrong.

____________________________________

GARDINER was also one of a group of LGBTI activists who campaigned for the Victorian Government to allow gay men with historical sex convictions to have their records expunged. In January, Victorian Premier Denis Napthine announced at the opening day of Midsumma, Melbourne’s LGBTI cultural festival, that his government would legislate to expunge these convictions.

The announcement was tied to the release of a report on the issue, developed by the Human Rights Law Centre and a number of state-based LGBTI organisations who had lobbied the government. Since then, other states have indicated they were looking to follow suit, with NSW most recently announcing it would develop similar legislation.

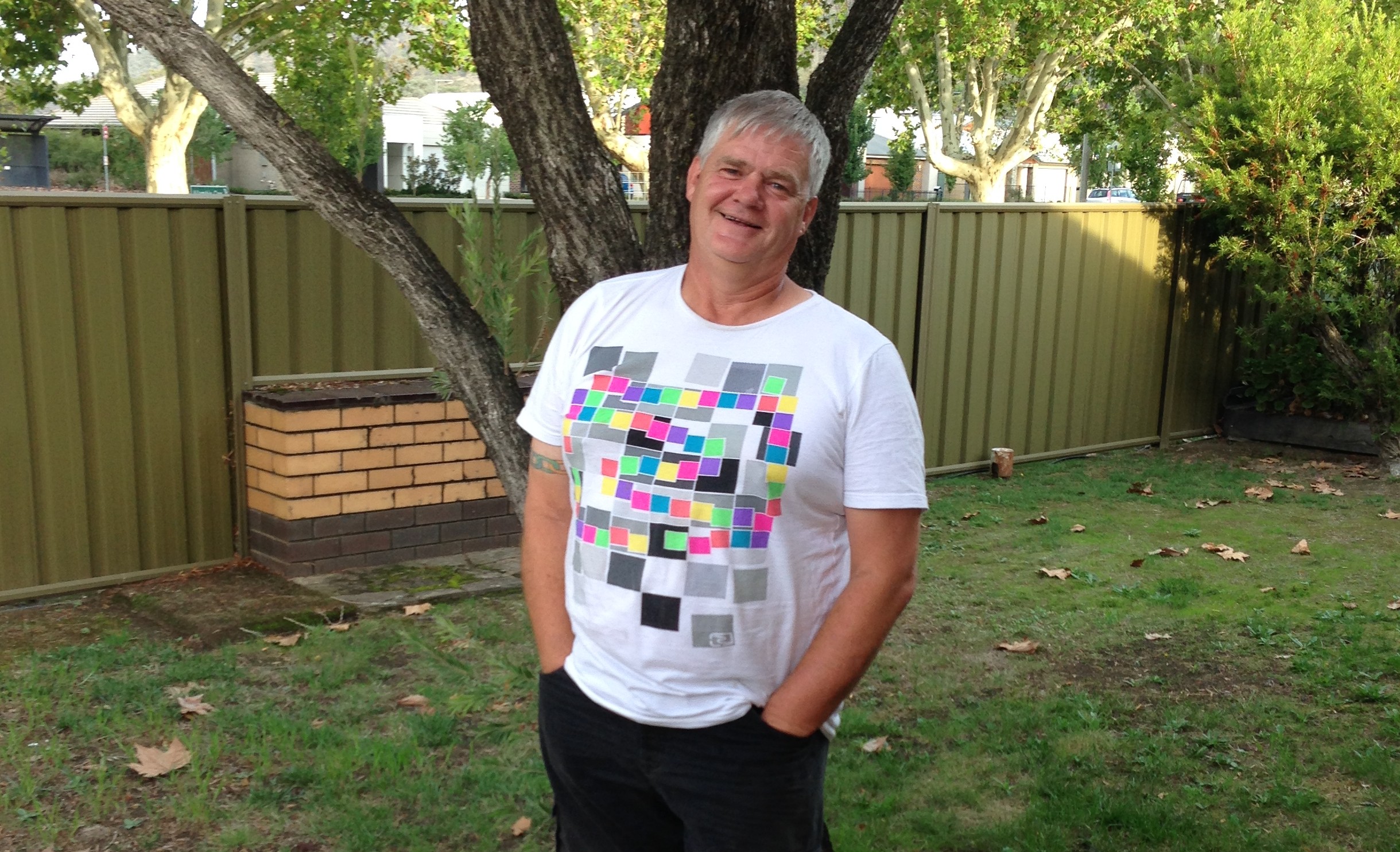

Although Tom never had his conviction recorded — only a verdict of guilt — he was heavily involved in the campaign in Victoria, doing several media interviews in the weeks following.

He found speaking about his ordeal exhausting and it took him some time to recover after each interview. Even building up the confidence to conduct the interview with the Star Observer took Tom weeks, after a number of bad experiences with other media outlets who cancelled interviews at the last second or interviewed him but didn’t run a story. He had organised for his sister to meet him after this interview, to make sure he would be okay.

Tom struggles on a day-to-day basis with the impact of what happened to him, and has lost all faith and trust in people in positions of authority.

“Every time I’m pulled over by the police, for a breath test or anything else, I become that 14-year-old boy again and I do not trust the police. Any police. I do not trust any member of the police force. I can’t,” he said.

“I don’t do friendships. I have very few friends because I can’t let them in. I’ve never been able to let them in. I have had failed relationships because I couldn’t let them in. One of my boyfriends said, ‘you’re making all this up, you’re just attention-seeking’. Needless to say that relationship didn’t last long.”

Eventually, Tom turned to drugs as a way to cope with the challenges of relationships.

“I just tried to forget about it, I threw myself into my work. But outside of work, until I discovered drugs I didn’t have a social life. And when I discovered drugs I went so heavily into it that I became a person I wasn’t,” he explained.

“That was never really me, it was all a façade.”

____________________________________

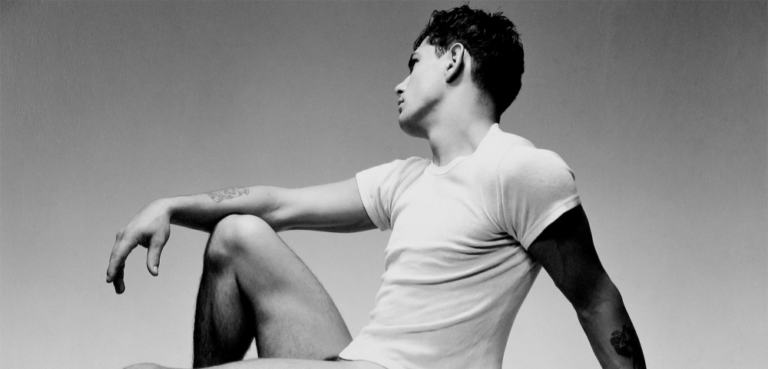

ALTHOUGH he grew up in Melbourne and lived there for years, Tom now lives in the north-east Victorian town of Wodonga, where he works with people living with disabilities. He said he loved his work and believed the abuse he suffered made him able to empathise more with people.

Wodonga isn’t very small, but through his media appearances since he went public with his story back in 2011, Tom has been recognised around the town.

“So many people have stopped me in the street and said, ‘I read your story in the paper and all I wanted to say was how brave and how courageous you are’,” Tom said.

Just weeks earlier, he had been recognised by a woman in a shop: “She said, ‘oh, that’s you. I was just reading your story, how sad.’ She said, ‘can I give you a hug?’ Because I put it out there, I’m getting so much support from people.”

Tom has been encouraged by the Victorian Government’s moves to expunge the records of men convicted under the same law as he was, but remained concerned initial proposals indicate those with convictions would need to apply directly for expungement.

“It’s not automatic. So people are going to have to go through and re-open all these old wounds again, and work out, is it really worth it? I’d pushed that pain so far down inside, and now just to get it expunged I’ve got to go back and prove to them that I was convicted,” he said.

“We are going to create a whole mess of anxiety and depression amongst victims for a second or third or fourth time, because of the way it’s being implemented.”

Gay Aboriginal activist and performer Noel Tovey expressed a similar concern in an interview with the Star Observer in February this year, when he compared such a process to older people’s discomfort at having to disclose their sexuality to government bodies like Centrelink. Tovey received a conviction for gay sex in 1951 when he was 17 years old, and has also been heavily involved with the expungement campaign.

“One time too many could be a breaking point. There could be suicides and breakdowns, because people are applying to the very system that let them down in the first place,” Tom argued.

“We’re being asked to take a leap of faith with a system that we have no faith in.”

For Tom, he feels the most important thing for his healing would be to receive an individual, face-to-face apology from the government: “My ultimate closure would be a face-to-face meeting with someone who has the power to say ‘Tom, we got it wrong, we are sorry’.”

____________________________________

TOM has never met any other men who went through similarly horrific experiences, but said he would love to talk to someone who would understand exactly what he went through.

Anna Brown, a lawyer from the Human Rights Law Centre, has been co-ordinating the involvement of Tom, Noel Tovey and other men with historical gay sex convictions. Tom praised her work and her support, and said he felt connected to these men through this experience, even if indirectly.

“She’s seen the similarities between all of us, in our personality traits: the high levels of anxiety that exist, the high levels of depression. The pain and the wounds that are forever opened up whenever we talk about it in-depth,” he said.

“We take ourselves back to a very dark place, and we then have to recover again. When it’s all over we have to find a way to recover and get through it and get back to our normal routine.”

Many men of Tom’s generation feel an acute generation gap around understanding the persecution and vilification of gay men in the past, and how much it has changed. Asked about this topic in his Star Observer interview, Noel Tovey said it was vital for young gay men to understand how the struggles of gay men in the past have made it possible for them to enjoy the life they have today.

This was echoed by Tom as one of the main reasons he felt so strongly about the need to tell his story publicly. He desperately wanted to communicate to young gay men today what it was like before, to encourage them not to take the astounding progress made on gay rights in Australia for granted.

“I talk to young gay guys now and they have no idea of what people have gone through just to get the rights they have now. We didn’t have technology. We didn’t have Grindr. We didn’t have chat rooms. We didn’t have anything like that at all. We had beats, or a few clandestine gay bars,” Tom said.